Everyone’s Journey, No One’s System: Can Bihar’s Transport Turn Sustainable?

By Akanksha Sinha

What is the Patna Pink Bus Initiative?

The morning sun hits Bailey Road as Drishti climbs out of her third auto of the day. Forty minutes for a seven km ride – all because there’s no direct bus to her college. Diesel fumes stall behind her, horn-blasts echo through the narrow lanes, and the city seems to say: you’re commuting – we’re just complicating it.

“Auto drivers even ask for unreasonable prices, par main late nahi ho sakti. Teen auto aur ek hi hope hai – time pe college pahunchna,” she says, adjusting her bag.

Sustainable transport in Bihar is more than policy – it’s a daily battle for those on the move. From students to working women and the elderly, the failing system costs more than minutes; it costs access, dignity, and equality.

On the other side of the city, Radha, a working woman in her 30s adjusts her dupatta as she squeezes into a crowded bus. She prefers buses over autos – cheaper, less risky. But comfort is a distant dream. “Kabhi seat milti hai, kabhi khade hone ki jagah bhi nahi,” she says softly. The Pink Bus was meant to change that. In Patna, the service offers women a rare sense of calm. “Yeh bus alag lagti hai,” said one commuter in a local article, “no fear, no stares – just a normal ride filled with women only.” But the problem is scale. Patna only has 30 pink buses on key routes. Safe and modern, yes – but far too few to meet demand. Many women from economically weaker sections, especially from smaller towns, remain unaware or unable to access the service.

Students like Fatima, a Class 12er at Patna Muslim High School, are discovering these buses for the first time. “Travelling with male passengers is sometimes uncomfortable; many times, I have faced hardships while travelling in other passenger vehicles. I came to know about the Pink Bus on Instagram and have asked my friends as well to try it out,” she said. She suggested: “The journey would be more pleasant and comfortable during summer if the buses were air- conditioned.”

Vidya Kumari waits at a roadside stop in Gaya, choosing her battles carefully. “I avoid overcrowded buses whenever I can,” she says. “But sometimes it means reaching late to work, or not going at all.” That late arrival can mean a pay cut, a missed client, or a teacher’s impatience. Small delays ripple into large losses.

Beyond the time lost, commuters face daily anxiety, harassment risk, fatigue, and lost opportunities. For many in lower-income households, a missed bus can translate into a missed meal or an unpaid bill.

And yet, amid the chaos, quiet attempts at solutions are beginning to emerge.

Small, Low-Cost Sustainable Solutions

As Drishti steps off her final auto and heads to class, Raju pulls his new e-rickshaw to the curb nearby. The hum of his battery-powered ride is almost gentle compared to the roar of diesel engines. “Diesel mehenga ho gaya, battery sasta hai — aur dhuaan bhi nahi hota,” he says proudly. He’s part of Bihar’s slow shift toward cleaner transport. E-rickshaws, CNG autos, and electric buses are beginning to appear — small but hopeful steps in a state still choked by fumes.

But not everyone’s journey is that smooth. Manoj, another driver, leans against his old fueled auto, eyes tired. “Socha tha electric auto lunga,” he says. “Par dekh bhaal mehenga hai aur charging stations bhi naa ke barabar hain”, his voice tinged with concern. “Fuel aur maintenance ke prices roz badh rahe hain. Passengers humpe chilla dete hain, kiraye pe ladte hain. Bas survive kar rahe hain,” Manoj says, his voice heavy with the strain of daily life.

The high initial cost of electric vehicles and the lack of adequate charging infrastructure pose significant barriers for drivers aiming to switch to greener alternatives (The Economic Times). Patna’s auto and e-rickshaw drivers even staged a strike, demanding better infrastructure, fairer policies, and adequate charging stations — a reminder that sustainability cannot thrive without supporting those who drive the change (Patnapress).

That frustration echoes across the lanes. Raju drives cleaner, but Manoj drives harder — each one trying to survive in a system that asks for change without giving them support.

When auto and e-rickshaw drivers went on strike, demanding charging stations and fairer policies, it wasn’t just a protest – it was a pause. Roads emptied, buses overflowed, and Radha’s commute doubled. “Hum samajhte hain unka dard,” she said, “par hum bhi toh suffer karte hain.”

That week, the city learned something simple: sustainability can’t move forward if the people behind the wheel are left behind.

As evening sets in, Raju parks his e-rickshaw near the charging point – a single socket shared by three drivers. The air around him is still thick, the sunset glowing through a dusty orange haze. “Main toh battery pe chalata hoon,” he says, plugging in the wire, “par hawa toh sabke liye kharab hai.”

A few lanes away, Manoj coughs softly as he refuels his old auto. “Cleaner gaadi lena chahte hain, par system hi saaf nahi hai,” he mutters, wiping his face with a handkerchief streaked with soot.

Both men, in their own ways, are trying to move forward – but the city seems stuck in its fumes.

To make this transition smoother, the government must do more than promote green slogans. Low-interest loans, battery subsidies, and technical training could ease the burden on drivers like Raju and Manoj. Expanding charging and maintenance networks across the city could finally help cleaner transport breathe freely.

Because right now, even as Bihar experiments with sustainability, its air tells a harsher truth.

Choking Commutes: The Price of Progress

By nightfall, the glow of headlights blurs into a smoky mist. What looks like fog is really the city exhaling its exhaustion. Patna’s air is among the dirtiest in the country.

Patna’s AQI often oscillates between ‘Unhealthy’ (AQI 151–200) and ‘Very Unhealthy’ (AQI 201–300), with occasional spikes into the ‘Severe’ category (AQI 301–400), especially during colder months. A significant portion of Patna’s polluted air comes from traffic: diesel buses, autos, and private cars emit high levels of PM2.5 and other toxins, frequently exceeding safe limits and harming public health.

Raju feels it every night when he heads home – a faint burn in his throat. Vidya, waiting for her late bus, covers her mouth with her dupatta. Drishti, cycling back from college, squints against the smog.

Studies acknowledge that transport contributes up to 19% of Patna’s particulate pollution. The cost of mobility now includes respiratory illnesses, lost productivity and increased healthcare expenses.

The same roads that move people forward are, ironically, what’s making it harder to breathe.

Back home, after another long day, Drishti lies on her bed scrolling through reels. One catches her eye – a smooth, silent bus gliding through Delhi traffic. The caption reads: “100% Electric, 0% Emission.”

She smiles faintly. “Patna mein bhi aise buses hoti toh?” she texts Fatima.

Fatima replies with another reel – Bengaluru’s clean, green bus stops, women boarding without a rush, kids cycling freely nearby. “Unke yahan sab connected lagta hai,” she says.

These short clips – small windows into better cities – spark big questions.

Lessons from Elsewhere: Learning Without Copying

Why not here?

As the reels keep rolling, the girls begin to see what works elsewhere – not just glossy visuals, but systems built with intent.

Cities like Delhi, Bengaluru, and Ahmedabad offer valuable insights into building sustainable, efficient urban transport:

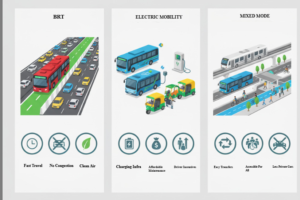

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT): Dedicated lanes in Ahmedabad and Delhi have cut travel time, reduced congestion, and improved air quality by separating buses from regular traffic. These systems show how prioritizing public transport over private vehicles can make daily commutes faster and cleaner.

Electric Mobility Integration: Bengaluru’s e-bus fleet and Delhi’s growing e-rickshaw network demonstrate that electric vehicles can significantly reduce emissions. But success depends on adequate charging infrastructure, affordable maintenance, and driver incentives — lessons Bihar must consider before scaling.

Mixed-Mode Systems: Delhi and Bengaluru integrate metros, buses, bicycles, and pedestrian-friendly roads. This multimodal approach enhances connectivity, making it easier for commuters to switch between modes, reduces dependency on private vehicles, and improves accessibility for all, including women, the elderly, and differently-abled passengers.

Watching these cities move forward on screen, Drishti pauses and texts, “Yeh sab copy karne ke liye nahi, seekhne ke liye hai.” Fatima replies “exactly”. Their chat drifts into ideas — shared e-rickshaw corridors for small towns, more Pink Buses for women like Radha, shaded waiting areas for workers who spend hours on the road.

Because Bihar’s solutions must rise from its own streets.

Local realities affordability, geography, commuter behaviour, and social structures – must guide every intervention. Smaller towns may gain more from shared e-rickshaws or mini-buses than from full-scale BRT corridors. And women’s safety, last-mile connectivity, and access for daily wage workers should be built into planning from day one – not added later as an afterthought.

The screen fades to black, but the thought lingers – Bihar doesn’t need to imitate others; it needs to imagine for itself. A city that listens not just to traffic, but to the people moving through it.

The next morning, Drishti scrolls through her college WhatsApp group between memes and assignment reminders. Later that day, while reading about Bihar’s transport issues online, she lands on Harit Safar’s website.

One article catches her eye — a recap of their “Yuva Samvaad on Clean and Inclusive Urban Mobility”. She clicks.

Photos show students marking unsafe routes on city maps, sharing stories about dimly lit bus stops and chaotic crossings.

“Dekha?” she texts Fatima, “They actually did this.”

People, Policy & Participation

Fatima opens the link too. Together they see — handwritten notes, sketches of bus routes, clusters of young faces determined to be heard. The dialogue took place months ago, but its energy feels current. The issues they raised — safety, accessibility, last-mile gaps — are still waiting for answers.

A few days later, I meet Drishti at her college canteen while working on my Harit Safar article about Bihar’s Pink Bus Service. The bustle of lunch hour hums around us.

She’s right. The women-only Pink Bus Service, launched by the Bihar State Road Transport Corporation, has given hundreds of women a pocket of safety — CCTV-fitted, GPS-tracked buses with female conductors with sanitary products available onboard, running on major city routes. But the comfort it offers is still confined to a handful of roads.

We talk about that gap — how some progress can still leave so many behind. Drishti scrolls back to the Harit Safar youth dialogue post. “Matlab log baat kar rahe hain,” she says. “Bas sunne wala koi chahiye.”

That’s where real participation begins — not when people are invited to speak, but when they’re finally listened to.

Because Bihar’s roads won’t truly change through policy alone. They’ll change when every commuter — driver, student, or working woman — starts noticing what needs fixing and dares to ask why it isn’t.

This brings us to the real hope ahead — collaboration. Bihar can truly progress when citizens, government, and policies work together in harmony to ensure sustainable and clean transport.

What Citizens Can Do?

Change doesn’t always begin in offices — sometimes, it starts at a bus stop.

Drishti notices a flickering light above the stop. Radha watches another overcrowded auto go by. Fatima wonders if her younger sister would ever feel safe travelling alone.

That’s where it begins — with people noticing.

Observe & Report: Spot broken bus shelters, dark corners, or unsafe spots. A single photo, a post, or a message shared online can make invisible problems visible.

Demand Inclusive Access: Ask simple questions: Are women safe? Can the elderly or differently-abled get on easily? Accessibility isn’t luxury — it’s the starting line of equality.

Choose & Push for Cleaner Commutes: Prefer public or women-only buses. Share rides, talk about clean transport, make it a conversation. Small choices, when repeated, create big change.

One evening, as I sit with Drishti and Radha at the bus stop, the conversation drifts beyond the wait. They talk about how travel has shaped their days — from fear to freedom, from fatigue to small victories.

Drishti smiles and says, “Har din kuch na kuch badal raha hai… chhoti cheezein hi sahi.” Fatima joins later on call, her voice bright. “Bas itna chahiye — ki humari baatein kisi tak pahuchein.”

I nod quietly. Maybe that’s where real change begins — in these small, persistent hopes shared between women waiting for a bus that’s running late, but still coming.

Evening settles over the city again. Raju parks his e-rickshaw near the charging point, wiping dust off the seat. A few meters away, Manoj leans against his old diesel auto, watching the line of Pink Buses pass by. “Badlaav toh ho raha hai,” he says, “bas thoda asaan kar dein humare liye.”

That’s where the government’s role becomes more than policy; it becomes partnership.

What the Government Should Do:

Listen to Citizens: Listen to those who live the commute every day — students who walk, women who wait, and drivers who keep the wheels turning. Harit Safar’s campus dialogues have already shown how citizen input can map unsafe routes and identify blind spots that planners miss.

Make Funding Fair: Budgets shouldn’t stop at buying buses or autos. They must fund safety and dignity — better lighting at stops where women stand after dark, training programs that help drivers like Raju switch to electric vehicles, and maintenance that keeps roads smooth enough for everyone.

Work With Local Groups: Collaborate with initiatives like Harit Safar and its Mobility Manifesto 2025. These frameworks turn local experiences — from commuters, drivers, and students — into workable blueprints. Policy should grow from lived journeys, not paperwork.

Manoj starts his engine again, coughing through the exhaust. Raju nods at him and says, “Ek din yeh dhuaan bhi khatam hoga.”

And maybe it will — when governance stops moving above the roads and starts listening to the ones driving on them.

Harit Safar’s Mission & Impact

As dusk settles over Patna, the city begins to quiet — just a little. Drivers switch off their engines, students step off buses, and the faint hum of evening traffic becomes background music. In a corner café, a group of young volunteers gathers around a map dotted with sticky notes.

It’s a Harit Safar meet — one of many across Bihar. Not a conference, not a protest — just people comparing notes, marking problem spots, and talking about change that should already have arrived.

While citizens, the government, and policies each play their part, Harit Safar has become the bridge between them — pushing for a green, inclusive, and climate-resilient transport system in Bihar.

Part of The Climate Agenda, its tagline says it all: “Sustainable Inclusive Mobility.”

What does Harit Safar do?

Spreads Awareness: It educates students, residents, and commuters about unsafe stops, overcrowded buses, and poorly lit streets, helping people understand transport challenges in their city.

Engages Youth: The initiative involves young people to highlight issues like last-mile connectivity, women’s safety, and access for differently-abled commuters, creating informed and active communities.

Influences Policy: Through the “Mobility Manifesto 2025,” Harit Safar provides recommendations to government and politicians, showing them how to make transport safer, fairer, and eco-friendly.

Focuses on Everyone: Emphasizes that clean and inclusive transport isn’t just about new buses—it’s about systems that serve pedestrians, students, women, daily wage workers, and differently-abled people.

Builds Community Action: By raising awareness and sharing knowledge, they encourage communities to speak up, suggest improvements, and demand inclusive, sustainable transport solutions.

Call to Action for Bihar 2025: Citizens, government, and political parties must come together to turn these ideas into a safe, inclusive, and sustainable transport system for all.

The cafe empties slowly. Raju stops by with his e-rickshaw to charge it nearby. Manoj waves from across the street. Radha messages that her bus finally arrived. Fatima sends a reel of the evening traffic with the caption: “Patna moves… slowly, but it moves.”

And in that motion — of stories shared, maps marked, buses filled — you can almost see Bihar’s transport changing shape.

From Drishti’s daily scramble to Radha’s quiet patience, from Raju’s switch to clean wheels to Fatima’s late-night texts, Bihar’s transport story is everyone’s story.

Wheels alone don’t move a city, people do.

And if Harit Safar has proven one thing, it’s that Bihar doesn’t need a revolution to move forward, just the courage to keep steering in the right direction.